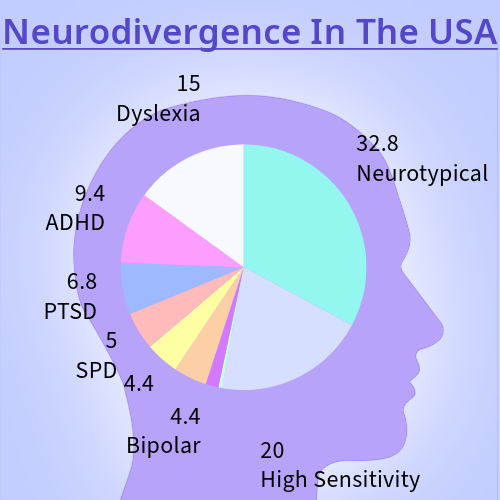

Schools across the country often promote an image of inclusivity, proudly displaying their commitment to supporting all learners. And to be fair, some truly do rise to the challenge-developing thoughtful strategies, honoring IEPs and 504 plans, and creating environments where neurodivergent students can thrive. But for many others, the gap between intention and implementation remains wide. Despite the legal frameworks in place, too often neurodivergent students find themselves underserved, with support plans that look good on paper but fail to meet real-world learning needs.

“I have heard on many different occasions students mentioning learning disabilities and 504 plans and many time teachers will just wave it off as something small or made up and because of that I have seen students that are really smart fail due to their needs not being properly meet, that’s why I believe that teachers overlook the learning plans,” said junior Samari Pearson-Porter.

When working with a service dog for over a year now in a school I’ve noticed how the school system truly acts. They would put me in a category with other neurodivergent students and treat me like I wasn’t my own person. I understand my disability is not a norm in today’s society, but many times I was treated like a child for having a disability and talked down to, been made fun of due to having a working dog or my disability in general, and dealt with harassment from students barking, meowing, and cat-calling my dog. I had to redo my 504 plan three times in one year due to teachers not following along with what I had in there, or wouldn’t follow or even read it.

As a student I shouldn’t have had to make a folder explaining what my disabilities were, my doctors note of my disability, 504 plan, and what my service dog does for me. Why should I have to do that, where is the ending line of fighting for one self?

Schools want to be inclusive but when we come to them about a teacher they overlook it until parents become involved. Is that intentional probably not, but where does this end?

School always said they want to teach kids to advocate for themselves and that they need to become adults cause that’s the next stage, but how can we do that when they don’t listen until a parent is involved? What about the students who can’t advocate for themselves, do they get pushed to the side?

Building substitute teacher Tiffeney Cox said, “To better accommodate neurodivergent students would be to get more teachers that are trained especially for neurodivergencies – they are not one size fits all. This doesn’t mean that teachers aren’t trained, but need more support inside a classroom.”

Cox works with many different students daily not knowing students needs, but she’s one of the realest one among substitutes who empathizes with the students. Cox is one of many teachers I talk to because she understands.

“Many teachers try to be inclusive but lack the support needed to follow through, especially if they have many neurodivergent students in each classroom and they become exponentially placed in each classroom yearly,” Cox said.

What happens now? How can schools move beyond simply writing policies and begin to genuinely accommodate neurodivergent students in meaningful ways by embracing practices rooted in empathy, implementing flexible approaches to learning and behavior, and fostering a deep, authentic understanding of neurodiversity within the entire school community?

One solution Pearson-Porter gave was, “schools can adopt a more inclusive learning environment by adding things to fidget with. Release energy in a effective and safe way. Teaching teachers when a student ‘misbehaves’ how to control the situations before coming to conclusions so quickly.”

While some argue fidgets are too expensive to provide for students, there are actually many budget-friendly options available at stores like Five Below or Dollar General, making it possible to supply these tools without a major financial burden. Fidgets don’t have to be high-end to be effective-what matters most is their ability to support focus and self-regulation in the classroom. Others express concern about fidgets being stolen or misplaced by students. However, instead of removing the resource altogether, we can implement a simple accountability system-like a sign-in and sign-out chart. This method, already used successfully in photography classes to track camera equipment, could easily be adapted for fidgets, helping promote responsibility while still giving students access to helpful tools.

To better support neurodivergent students, schools must move beyond one-size-fits-all approaches and embrace inclusive practices across the board. This includes adopting Universal Design for Learning to offer flexible teaching and assessment methods, creating sensory-friendly environments with quiet spaces and tools like noise-canceling headphones, and establishing clear, predictable routines.

Schools should shift away from punitive discipline and instead use restorative practices that consider neurological differences. Staff need ongoing training in neurodiversity, communication styles, and sensory processing, while students should be educated to foster understanding and reduce stigma.

Most importantly, neurodivergent students deserve a voice in shaping their educational experience through feedback channels and involvement in IEP or 504 planning. Inclusion isn’t just a policy—it’s a daily practice that transforms lives.

I think it’s time for schools to stop expecting all students to learn the same way. We call on educators, administrators, and policymakers to implement flexible teaching methods that everyone has to follow even if they don’t believe in it, provide sensory-friendly environments, recognize diverse communication styles, and include neurodivergent students in decision-making processes.

Neurodiversity is not a flaw—it’s a strength. Let’s build a school system that celebrates and supports all kinds of brains.